‘Take for example the city.. it consists of squares, streets, dead-ends…one can move about, pause, start again. The museum that finds inspiration in the form of cities acknowledges the alternation of motivation, interest, and fatigue. It is a system of galleries; lofty spaces, intimate rooms that relate and alternate to each other. One should have the possibility of losing oneself …. The museum must offer visitors a loose thread to follow….’ – Pontus Hulten (Hulton, 1976)

When The Tate Modern opened in 2000, it faced controversy within the art sphere as it was located in the former industrial Bankside Power Station. Prior to this, art was most traditionally displayed in purposefully built galleries so therefore, this was a turning point for galleries/museums to be housed in regenerated urban environment. However, this move was met with many criticism. As journalist John Loughery wrote, “Art is fragile, architecture is not… the weight of the Tate Modern as a building that won’t stop speaking to us so that we can attend to the art… is crushing”. In other words, he believed that a building such as The Tate Modern’s is distracting to the artwork shown and should be a less prominent feature. Despite this, the project was proven more successful than even the project director had envisioned, drawing over 5 million visitors on the first year and continues to attract more annually, ranking among the top 5 museums and galleries. (A new vision for Tate Modern, 2016)

As this building was originally constructed for industrial use and was filled with many large machinery, the designers of The Tate Modern were met with many difficulties regenerating the environment for public usage. Although stripped bare from any original machinery, The Tate Modern still keeps many original exterior and interior features such as the old steel beams within The Turbine Hall that greatly juxtaposes the modern artwork on display.

The enormous Turbine Hall is a prominent feature of The Tate Modern, appropriately named as such as it originally housed the turbines in the factory. Currently stripped down to it’s structure, the hall gives a euphoric atmosphere like that of a cathedral with high, elongated window similar to stained glass windows. Additionally, the grand openness of the hall gives plenty of space for ever-changing commissioned artists to experiment with exciting art projects on a large scale.

In 2006, The Tate Modern commissioned artist Carsten Höller to install 5 large engaging spiraling slides in The Turbine Hall with one on each floor from floor 2 upwards. This installation became successful, creatively combining art with enjoyment for children and adults alike. Höller explains that the ‘installation is very spectacular, as you said, because the performers become spectators (of their own inner spectacle) while going down the slides, and are being watched at the same time by those outside the slides.'(Honoré, n.d.). Additionally, this project (aptly named ‘Test Site’) was created as an experiment to investigate slides being a part of permanent architectural structure and whether they can be established for regular daily urban functions. As Höller further explains, ‘I see one function of the museum as being a space for experimentation and for testing ideas and concepts that could eventually be realised on a larger scale outside the museum.’ (Honoré, n.d.) Thus, The Tate Modern gives a great platform in which artists can experiment and expand for further projects.

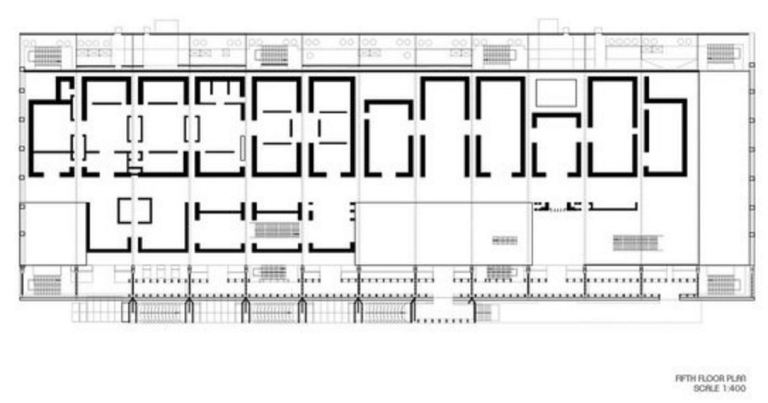

Despite The Tate’s installation of many interactive art, the layout of the gallery is rather restrictive with controlled visibility of artworks compared to many other museums. This contrasts Hulten’s view that galleries should be a place to be able to move independently unlike that of a restrictive city plan. Professor of Museology, Kali Tzortzi, compared The Tate Modern’s structure to that of The Pompedou in Paris. (Tzortzi, 2010) She wrote that although the two galleries bares many similarities in that they are both modern galleries built within the city with a similar grid like structure, the layouts of the rooms and their effect differs. The Tate Modern lacks the same symmetry of The Pompedou and the rooms are organised so that the visitor follows a curated and narrated sequence of rooms. On the contrary, The Pompedou’s layout is created so that the visitor is able to freely choose their own route within the galleries, with the ability to omit areas at one’s own leisure. However, Tzortzi also argues that with the visitor urged to make decisions on movement in The Pompedou, requires a higher degree of intelligent thinking and interpretation of the artwork displayed.

The Tate Modern’s development benefited the city greatly as it influenced interest and business within the area that was otherwise desolate. It’s idea location close to transport systems and accessible approach to design, makes it easy to appreciate by a wide audience including those that are not familiar with art. Although it was over a decade ago when the slides installation was placed, and I was only 11 years old at that time, I remember the experience that I enjoyed to this day as there is no other institution alike. To go to The Tate is an engaging experience and with the Tate Modern recently completing a new development by building an extension to the space, it shows that it continues to strive with future-thinking ideas for galleries.

Further Reads:

Artists’ Ideas on the Future of Museums

Audio of the Chief Designer (Jacques Herzog) on the Challenges of Constructing The Tate Modern

Tzortzi’s Paper on the Comparison of The Tate Modern and The Pompidou

What Colour Should Gallery Walls be?

Sources:

A new vision for Tate Modern. (2016). [online] Tate. Available at: http://www.cnbc.com/2014/03/05/hack-this-conversation-and-more-overused-words.html [Accessed 22 Oct. 2016].

Honoré, V. (n.d.). Carsten Höller: Interview. [online] Tate.org.uk. Available at: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/unilever-series-carsten-holler-test-site/carsten-holler-interview [Accessed 1 Nov. 2016].

Hulton, P. (1976). Beaubourg et son musée où explosera la vie. Réalités,. p.337.

Tzortzi, K. (2010). The art museum as a city or a machine for showing art?. [online] Space Syntax Symposium. Available at: http://www.sss7.org/Proceedings/04%20Building%20Morphology%20and%20Emergent%20Performativity/117_Tzorti.pdf [Accessed 1 Nov. 2016].

Loughery, J. (2001). The Future of Museums: The Guggenheim, MoMA, and the Tate Modern. The Hudson Review.